July 21, 2012 · 9:34 am

I have been featuring fantastic female fantasy authors (see disclaimer) but this has morphed into interesting people in the speculative fiction world. Today I’ve invited the talented Helen Lowe to drop by.

Watch out for the give-away question at the end of the interview.

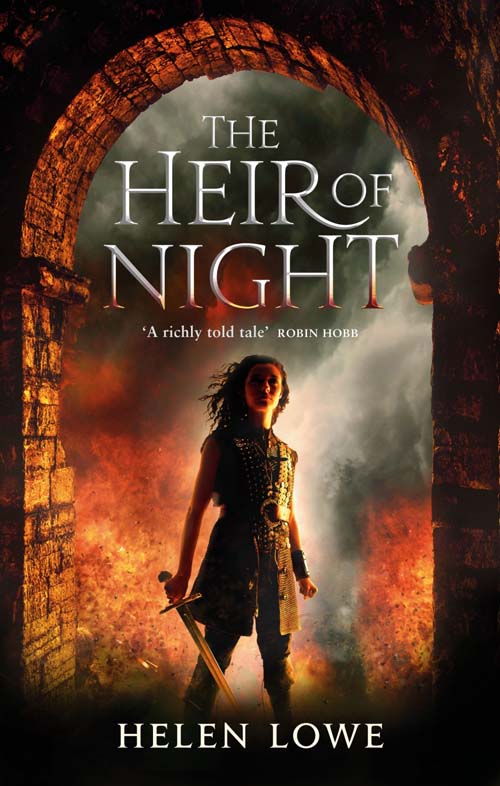

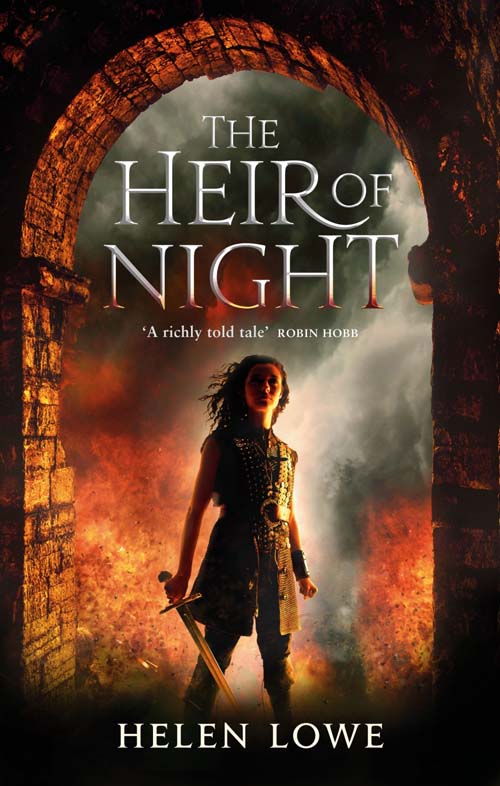

Q: First of all congratulations on The Heir of Night (The Wall of Night series) winning the David Gemmell Morningstar Award. (For a full list of Helen’s awards see here). But you’re not new to winning awards. Your work has twice won the prestigious Sir Julius Vogel Award and your first win was in 2003 with a poem. Rain Wild Magic won the “previously unpublished” category of the Robbie Burns National Poetry Competition. Do you think winning awards helps writers reach readers?

Helen: Rowena, thank you regarding the Morningstar Award. Getting the news that The Heir of Night had won was quite a buzz, especially since I was “pretty sure” that it was the first Southern Hemisphere-authored book, and I was the first female writer to have won in either of the two Gemmell Award book categories. (I have since confirmed that this is in fact the case.) So it was nice to feel that The Heir of Night had managed to carry the flag through on both those fronts.

Helen: Rowena, thank you regarding the Morningstar Award. Getting the news that The Heir of Night had won was quite a buzz, especially since I was “pretty sure” that it was the first Southern Hemisphere-authored book, and I was the first female writer to have won in either of the two Gemmell Award book categories. (I have since confirmed that this is in fact the case.) So it was nice to feel that The Heir of Night had managed to carry the flag through on both those fronts.

In terms of what difference winning awards makes, I don’t really know, to be honest. The Booker and Orange Prizes seem to get a fair bit of attention, both from the media and book shops, but my impression is that most other awards don’t. So I’m really “not sure” in terms of reaching out to a wider readership beyond those who are already savvy to the awards.

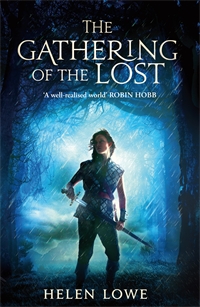

Q: The second book in The Wall of Night series, is The Gathering of the Lost. I see you use the word series, rather than trilogy. Does this mean that each book is self contained and you plan to write one a year (or more?).

Helen: The Wall of Night series is actually a quartet, but pretty much I am using the terms ‘quartet’ and ‘series’ interchangeably… In fact The Wall of Night (series or quartet) is one story told in four parts, rather than four self-contained stories – in much the same way, I think, that The Lord of the Rings is one story told in three parts. Having said that, each of the four parts of The Wall of Night story has a slightly different focus, as well as being part of a continuing arc, so I believe that may give each book a distinct character.

Q: You’ve been awarded the Ursula Bethell/Creative New Zealand Residency in Creative Writing 2012, University of Canterbury. This lasts from January to June. What exactly does it entail? Do you write madly for six months? Do you teach as well?

Helen: The main idea is that I write madly for six months, which is what I have been doing – and get paid to do so, which as other writers out there will know is a pretty amazing feeling! There is no specific teaching requirement, but I have run three sessions for creative writing students focusing on my practical experience of “being a writer.” I will also do a seminar for the College of Arts’ scholarship students before I complete my term.

Q: Thornspell is your retelling of Sleeping Beauty from the prince’s point of view. What intrigued you about the prince’s side of the story?

Helen: The idea for the story first came to me when I was at a performance of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ ballet. I recall the moment when the prince first leapt onto the stage and I sat up in my seat and thought: “What about the prince? What’s his story?” The main character of Sigismund (the prince), the world, and the central thrust of the story all flashed into my head in that instant. But I think the main ‘hook’ was that first moment of realising that no one had ever told the prince’s story before, that he is mostly a deus ex machina to the traditional tale.

Helen: The idea for the story first came to me when I was at a performance of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Sleeping Beauty’ ballet. I recall the moment when the prince first leapt onto the stage and I sat up in my seat and thought: “What about the prince? What’s his story?” The main character of Sigismund (the prince), the world, and the central thrust of the story all flashed into my head in that instant. But I think the main ‘hook’ was that first moment of realising that no one had ever told the prince’s story before, that he is mostly a deus ex machina to the traditional tale.

I subsequently learned that Orson Scott Card had written a novel, Enchantment, that is partly based on Sleeping Beauty and told from a male perspective – but it is tied in with several Russian folk stories and much less recognisably Sleeping Beauty, I feel.

Q: In an interview on the Pulse, you say the world of Thornspell ‘is loosely based on the Holy Roman Empire during the Renaissance / early Reformation period – not in terms of events, but in terms of cultural geography and technology, such as how people lived, clothes, weapons, tools, and learning. I think that helps to “ground” the story for the reader’. Are you a big fan of history? Do you travel to real places to get the feel of them and walk through restored castles?

Helen: Rowena,I love history and read non-fiction history as well as historical novels. And yes, I do love visiting cultural and historic heritage sites when I travel, and to date have visited castles and similar in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and Japan. But while visiting sites can give you historical ‘flavour’, which is important, I also draw on primary and secondary accounts and research as required, which I feel can be just as important for authenticity. Another important element for me is the literature of the times, which helps give a feeling for what contemporary people thought and felt was important – for example works like the Anglo Saxon Beowulf, or the medieval Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, or going further back, the Greek tragedies, or The Iliad.

Q: Thornspell is a Young Adult book. Did you set out to write a YA story, it did it just develop this way?

Helen: You know, I really didn’t. I tend to just write the stories “as they come” – but having said that, the ‘shape’ of the story did come clear fairly quickly. I would say that by the end of the first chapter I knew that it was “Kid’s/YA.”

Q: I was prompted to start this series of interviews because there seems to be a perception in the US and the UK that fantasy is a bit of a boy’s club. Do you think there’s a difference in the way males and females write fantasy?

Q: I was prompted to start this series of interviews because there seems to be a perception in the US and the UK that fantasy is a bit of a boy’s club. Do you think there’s a difference in the way males and females write fantasy?

Helen: If that is so, regarding the boys’ club perception, then I have to say I believe it is a completely false premise. In my experience, just as many women read Fantasy (and Science Fiction) as men, and what most men and women I know are reading overlaps to at least 80% – maybe even 90%.

In terms of my judgement as to whether there is a difference between the way women and men write Fantasy… I have never really analysed this so I have to go off ‘what I personally read and like’ and my feeling is that I can’t point to any substantive differences… For example, I love richly written, High Romantic Fantasy and both Patricia McKillip and Guy Gavriel Kay equally tick that box. I also like intricately plotted works that twist and turn, but can I pick between CJ Cherryh and Patrick Rothfuss? For character-driven storytelling: Daniel Abraham or Ursula K Le Guin? For adventurous storytelling: Barbara Hambly or Tim Powers? Even with gritty realism, sure there’s George RR Martin, but there is also Robin Hobb with her “Assassin” series. And although one may point to China Miéville for sheer imagination, the same applies to Elizabeth Knox with her “Dreamhunter / Dreamquake” duology.

Thinking as I go along here, if there is one difference that I might possibly point to – and without doing an exhaustive survey I can’t be sure – I suspect female authors “might” be found to use the first person point of view more. But it’s by no means an exclusive preserve!

Q: Following on from that, does the gender of the writer change your expectations when you pick up their book?

Q: Following on from that, does the gender of the writer change your expectations when you pick up their book?

Helen: No, absolutely not. I make my ad hoc reading choices (as opposed to books sent to me for review/interview) on the basis of three criteria: i) does the cover speak to me ‘across a crowded bookshop’ and draw me in? ii) Does the back cover blurb appeal? iii) When I read the first few paragraphs to pages, am I hooked enough to either buy the book or check it out of the library (depending on my locale at the time)? And that’s it. I pay very little regard to who the author is (except of course for when I’m looking for the ‘next’ book by an author I already follow) or to “quotes” by other writers or reviewers.

In terms of prejudging a book by the sex of the author, I really do think that’s a fairly foolish approach given the number of authors who write under pseudonyms. And even if I had been inclined that way, I think discovering that one of my favourite authors of “women’s historical romantic fiction” when I was a teen, Madeleine Brent, was in fact a man, would have cured me of it!

Q: And here’s the fun question. If you could book a trip on a time machine, where and when would you go, and why?

Helen: That’s an interesting question… You know, I think I might try for something like five hundred years in the future, just to see how we’ve evolved – whether we’ve managed to turn around what appears to be our current desire as a species to ‘trash’ our own planet, which in universe terms does appear to be something of an ark. And if so, how we’ve done it. As well as whether we have managed to get off-planet in any significant way. In other words, that good old spec-fic fall back: I want to check out the space travel!

Give-away Question: Helen: OK, given we’ve talked about The Heir of Night winning the Gemmell Morningstar Award, I have a copy of the book to give away, to be drawn from commenters who respond to this question:

Give-away Question: Helen: OK, given we’ve talked about The Heir of Night winning the Gemmell Morningstar Award, I have a copy of the book to give away, to be drawn from commenters who respond to this question:

On your voyage to Mars, what three Fantasy novels would you absolutely not be without – and why?

Follow Helen on Twitter: @helenl0we

See Helen’s Blog

Catch up with Helen on GoodReads

Listen to the SF Signal Podcast with Helen

Filed under Australian Writers, Awards, Book Giveaway, creativity, Fantasy books, Female Fantasy Authors, Gender Issues, Nourish the Writer, Writers and Redearch, Young Adult Books

Tagged as David Gemmell Morningstar Award, Helen Lowe, The Gathering of the Lost, The Heir of Night, Thornespell

July 18, 2012 · 8:35 am

Late in June, I placed the seventh novel bearing my name onto the bookcase in my living room. A few days later, a reporter from my local newspaper came by, took a photo of me standing in front of the bookcase, and asked a question that I should be a lot better at answering by now. What inspired you?

Late in June, I placed the seventh novel bearing my name onto the bookcase in my living room. A few days later, a reporter from my local newspaper came by, took a photo of me standing in front of the bookcase, and asked a question that I should be a lot better at answering by now. What inspired you?

The novel in question is Hush, the second book in my Dragon Apocalypse series from Solaris Books. I was tempted to explain my inspiration on most crass level, explaining that I wrote it to make money! I signed a contract with Solaris to write them three novels in exchange for some dough. I like to keep keep my promises.

But, there are lots of ways to make money. And, a nearly infinite number of possible books to write. So why Hush?

My second inspiration for Hush was to write a book unlike anything else I’d ever tackled before. This was a tough goal. As the second book of a series, Hush featured the same protagonist, the same narrator, and the same fictional universe as Greatshadow. The first book built up to a big fight with a dragon; the second book builds to a big fight with a couple of dragons.

Knowing that I was constrained by these structural similarities, I decided to keep things fresh by writing way, way outside my comfort zone. For Hush, I decided that reality was a crutch for those who can’t handle fantasy and decided that, if I were going to write in a fantasy universe, I’d write in a world defined by myth rather than bland and neutral laws of physics. In our world, the sun is a giant ball of gas that appears to cross our sky because our planet spins. In the world of Hush, the sun is a big-ass dragon living inside a giant, glowing pearl that sails across the blue waters of the Great Sea Above. At night, when the dragon rests, the dark sea begins to freeze. The stars are merely ice floes drifting in the currents of the ocean overhead.

Knowing that I was constrained by these structural similarities, I decided to keep things fresh by writing way, way outside my comfort zone. For Hush, I decided that reality was a crutch for those who can’t handle fantasy and decided that, if I were going to write in a fantasy universe, I’d write in a world defined by myth rather than bland and neutral laws of physics. In our world, the sun is a giant ball of gas that appears to cross our sky because our planet spins. In the world of Hush, the sun is a big-ass dragon living inside a giant, glowing pearl that sails across the blue waters of the Great Sea Above. At night, when the dragon rests, the dark sea begins to freeze. The stars are merely ice floes drifting in the currents of the ocean overhead.

The sun-dragon, Glorious, makes his journey across the heavens on a regular schedule because he’s something of an obsessive-compulsive. He was born into a world where the sun was an untamed thing that would drift across the sky at random intervals. There was no such thing as time. Glorious looked at the chaotic world that surrounded him, a world lacking predictable patterns of night and day and seasons, and thought that it would much easier to organize his thoughts if the movements of the sun could be made to follow a schedule. So, he flew from the material world to the Great Sea Above where he took up residence inside the pearl, steering it onto a predictable path and pace to satisfy his longing for order. In doing so, he accidentally created human civilization, since the ape-like creatures that once hunted and gathered in the timeless world discovered that, in a world with set day lengths and predictable seasons, it was easier to grow food than to hunt for it.

Alas, one dragon who wasn’t happy about Glorious flying off to live in the sky was Hush, who was deeply in love. Her affection for Glorious was unrequited, however, and when he abandoned the world her heart shattered. Bitter cold filled the void where her heart had once been, and she became the primal dragon of cold. Each year, she grows angry with Glorious as he warms the earth to the point that nearly all ice begins to melt. In her wrath, she begins to chase the sun as he crosses the sky, leading to shorter and colder days, weakening Glorious to the point that, in the northern realms, he disappears from the sky completely. With her wrath abated for the moment, Hush returns to her abode to rest, allowing Glorious to timidly return to sky, regaining his strength until it’s once again summer, and Hush’s hatred once more drives her to pursue him.

I was inspired to create this myth by the very roots of fantasy, the various mythologies—Greek, Norse, Egyptian, Asian—that form the foundations of our shared literature and also much of our shared morality. From our modern perspective, the material world may be understandable, but it’s under no obligation to make sense or have meaning. There’s not a lot of moral knowledge to be gained from knowing that the sun and stars are distant balls of hot gas. The idea that the heavens were the abode of gods, and that we might learn from their stories, now seems quaint. But, these myths continue to resonate on an emotional level. There’s something deeply satisfying about looking at a night sky and thinking of it as a canvas for sagas of love and betrayal, cowardice and courage. I’m hoping to capture a bit of this mythic grandeur in my tale of dueling dragons and the humans swept up in their battles.

Why do myths have such a hold on my imagination? Remember that bookcase I was standing in front of? If my novels were the only books it held, the shelves would be pretty empty. Instead, they’re packed, with Poe and Pratchett, Bullfinch and Burroughs, Sagan and Segar. While the middle shelves are full of hardcovers, the highest shelf I’ve reserved for old, dusty paperbacks, many rescued from my grandfather’s porch. He was a voracious reader who fed his appetites by scouring thrift stores and yard sales and buying paperbacks for pennies. His collection spilled out of his house and onto his porch, where I would spend much of my childhood digging among these yellowed pages looking for science fiction and fantasy novels.

It was the beginning of a lifelong love of words. It’s fun to see my books in bookstores, but some of my best experiences as an author have come when I discover used copies of my books in second hand stores. I remember the first time I found a copy of Bitterwood for sale in a thrift store, with a broken spine and dog-eared pages, waiting for some cheap but voracious reader to pick it up for a couple of quarters. There’s nothing wrong with loving books as objects, collecting hard covers still in their original jackets for prominent display in your living room, a monument to a work of literature that was important to you. But, for me, the most beautiful books have torn covers and browning paper, worn from having been read and reread by multiple readers. The pages may be half way to dust, but the words lived for a moment, at least, in someone’s memory.

It was the beginning of a lifelong love of words. It’s fun to see my books in bookstores, but some of my best experiences as an author have come when I discover used copies of my books in second hand stores. I remember the first time I found a copy of Bitterwood for sale in a thrift store, with a broken spine and dog-eared pages, waiting for some cheap but voracious reader to pick it up for a couple of quarters. There’s nothing wrong with loving books as objects, collecting hard covers still in their original jackets for prominent display in your living room, a monument to a work of literature that was important to you. But, for me, the most beautiful books have torn covers and browning paper, worn from having been read and reread by multiple readers. The pages may be half way to dust, but the words lived for a moment, at least, in someone’s memory.

And ultimately, that’s my inspiration for writing books. Seeing them in bookstores is fine. But, I still dream that, one day, some bookish kid might be digging through a stack of dusty paperbacks on his grandfather’s porch and find a book of mine, and bring the words inside to life once more.

James is giving away a copy of Hush.

James is giving away a copy of Hush.

What is your favourite Greek Myth

Filed under Book Giveaway, creativity, Nourish the Writer, Tips for Developing Writers

Tagged as Bitterwood, Book Giveaway, Dragon Apocalypse, Fantasy books, GreatShadow, Hush, inspiration, James Maxey, Writing craft

July 11, 2012 · 9:07 am

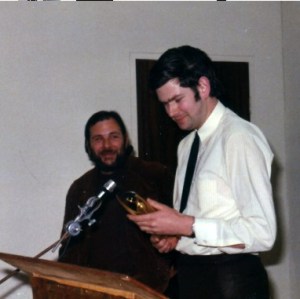

Bruce with Apple Blossom (1977)

I have been featuring fantastic female fantasy authors (see disclaimer) but this has morphed into interesting people in the speculative fiction world. Today I’ve invited the hardworking and insightful Bruce Gillespie to drop by.

I first met Bruce in 1976, when I went to Melbourne with Paul Collins to start an Indie Press publishing house. Bruce was living in Carlton with his cat Flodnap (and his cat’s cat, Julius) and had been editing fanzines for 8 years. By 1976, Bruce had been nominated for a Hugo three times, so despite being only 29, he was already one of the Grand Old Men of Australian SF Fandom.

Q: Your work had received three Hugo Nominations before you were 30. You have received total of 45 Ditmar Nominations and 19 wins, and The A Bertram Chandler Award in 2007, plus you were fan guest of honour at AussieCon 3, the World SF Convention in 1999, is there anything left that you would like to achieve?

A: Like any other fanzine editor or writer, I would actually like to win the Hugo Award for either Best Fanzine or Best Fan Writer! But that seems impossible these days, since even in 1999 and 2010, when the world convention was held in Australia, I could not gain enough votes to reach the nominations list.

A: Like any other fanzine editor or writer, I would actually like to win the Hugo Award for either Best Fanzine or Best Fan Writer! But that seems impossible these days, since even in 1999 and 2010, when the world convention was held in Australia, I could not gain enough votes to reach the nominations list.

Bruce receives his first Ditmar from John Bangsund (1972)

However, in 2009 I was awarded the Best Fan Writer in the annual FAAN Awards, given by my peers, the fanzine writers and editors who attend the Corflu convention in America. I count that as a great honour, along with having received Australia’s two awards for lifetime achievement, the A. Bertram Chandler Award (as you mention) and the Peter MacNamara Award. In practical

terms, the greatest honour I’ve received was the Bring Bruce Bayside fan fund, which enabled me to return to America (for the Corflu and Potlatch conventions) for a month in 2005.

- The Gang (1967)

John Bangsund, Leigh Edmonds, Lee Harding, John Foyster, Tony Thomas, Merv Binns and Paul J Stevens

- The Gang (1967)

Q: In your 2012 snapshot interview you say: A fanzine is a minor artform, based on putting together a wide range of material from my favourite writers, plus response from letter writers from all over the world. The use of a computer limits the artform in some ways, but also offers design, editing and font possibilities that were impossible to access in the Good Old Days (pre 1990s) of using stencils and duplicators.’ You have been producing zines now since 1968, that’s 44 years. In that time you must have worked out what makes a good fanzine. If you could go back now to Bruce circa 1968, what advice would you give him?

A: I could have warned him not to use the typewriter with which I produced the first SF Commentary in 1969. It was a little Olivetti with a beautiful typewriter face — but unfortunately it would not cut a stencil properly. For a fanzine that was almost illegible, SF Commentary No 1 gained an enormous response from people around the world, including a letter from Philip K. Dick, my favourite SF writer.

A: I could have warned him not to use the typewriter with which I produced the first SF Commentary in 1969. It was a little Olivetti with a beautiful typewriter face — but unfortunately it would not cut a stencil properly. For a fanzine that was almost illegible, SF Commentary No 1 gained an enormous response from people around the world, including a letter from Philip K. Dick, my favourite SF writer.

But apart from that, how can you give advice to a 22-year-old, especially someone with far more energy than I have now? ‘Follow your nose?’ ‘Never give up?’ I knew then that no matter how people responded to my fanzines, that was what I should be doing. Nothing’s changed.

Bruce with Brian Aldiss at Stone henge (1974)

Q: In the same interview you said: ‘Of course, I can publish electronically, using PDF files, on Bill Burns’ wonderful efanzines.com, but I know that many people download such magazines and don’t read them with the attention they would devote to a magazine they received through the mail.’ I do most of my reading on-line, following science blogs, political activists and researching. Personally, I don’t feel that I give less attention to my on-line reading. What leads you to believe that an on-line magazine is valued less than a print magazine?

A: For someone of my generation, a paper document has real existence, and online documents don’t. I don’t really believe that the current electronic publications will be available or readable in twenty years, let alone forty, but I still own almost all the paper fanzines I’ve received since 1969. If I value anything I find Out There, I copy it into a Word file and print it. More to the point, many of my correspondents say that they reply to paper fanzines, and don’t respond to fanzines posted on efanzines.com. That’s if they even take the trouble to download.

The current situation is that I can no longer afford to print and post my fanzines, so I will be asking almost all my readers to download them. This will sharply reduce the number of letters of comment I receive, but it gives me much more freedom to publish much more often.

Q: You once said about Fandom: ‘Before I joined fandom I had almost no friends or anybody with whom I could share my interests. In fandom I found people who were not just another part of the mundane world, which I find stifling. During a weekend I spent at Lee Harding’s place in late 1967, I met for the first time many of the people who have had the most influence on my life, such as John Bangsund, Lee Harding, George Turner, John Foyster and Rob Gerrand.’ (See Bruce’s post about science fiction and fandom here). I must admit that it wasn’t until I came to Melbourne with Paul in 1976 that I met people I could talk to. I’d come from Brisbane where all people talked about was football and getting drunk (obviously I was moving in the wrong circles). In Melbourne fandom I met fascinating people who could hold stimulating conversations on all manner of topics. I felt like I’d come ‘home’. Nowadays with the WWW people can make contact with other like-minded people, but forty years ago it was much harder. SF fans were considered extremely odd. Can you give readers a glimpse of what it was like to be a fan in those days?

Melbourne Fandom in 1954

Back row: Merv Binns, and Dick Jenssen

Front row: Bob McCubbin, Bert Chandler and Race Mathews

A: At school, I had only two friends who read science fiction at all. Nobody else I knew read SF, although the SF magazines were much more widely available (in newsagents) than now. At university, no other students seemed interested. However, I did read in the Bulletin in 1966 that Melbourne had just held an SF convention. Charles Higham wrote what remains the fairest report any Australian journalist has ever offered of an SF convention. He made it sound very exciting. I also knew that the Melbourne SF Club held its meetings every Wednesday night in Somerset Place, which was behind McGill’s Newsagency in Elizabeth Street. McGill’s had the only good stock of science fiction in Melbourne, and I realised that this had something to do with the tall thin man who loomed behind the counter (who was, of course, Mervyn Binns, who has just been given the Infinity Award for his services to fandom). Every science fiction book sold in McGill’s included a little leaflet advertising the club. Also, McGill’s sold a magazine called Australian Science Fiction Review (ASFR). The quality of the reviews and articles in this magazine were staggeringly far ahead of those in the pro SF magazines, for both intellectual content and sparkling style. However, I knew I would never finish my degree if I became involved in fandom from 1965 to 1967. At the end of 1967 I wrote several articles on the works of Philip K. Dick and sent them to John Bangsund, the editor of ASFR. He rang me in December 1967 and suggested I visit his home in Ferntree Gully to meet the people who produced the magazine. This was the beginning of my career in fandom, for I met people who read what I read, talked about what interested me, and who were interested in what I had already written.

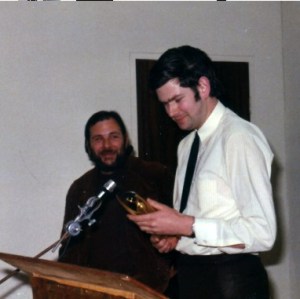

Bruce with Allan Sandercock (1971)

Q: You are a qualified school teacher and did teach for two years, but gave it up to produce fanzines and write about speculative fiction. You said: ‘My mundane career has never gone anywhere much, and I’ve often been nearly broke. But my career in fandom (as an editor), which has never made me any money, has led to most of the good things in my life.’ What do you think are essential traits an editor needs?

A: That’s not quite right. I gave up teaching because I was hopeless at it. I was very close to suicide at the end of 1970, but a friend prompted me to do what I would have thought unthinkable — resign. When I did this, the Department wanted to keep teachers, so I was offered a series of bribes to stay officially a teacher. The last of these was a position in the Publications Branch of the Department. In 1971 and 1972 I received a full on-the-job training in professional editing and journalism. I left in mid 1973 to go overseas, visiting fans all over America for four months and a month in Britain. When I returned I decided to try freelance book editing. I knew there was no editing work in SF in Australia, but my friend John Bangsund was making an intermittent living from freelancing, and there was plenty of work, especially in textbooks, in 1974.

The essential quality of an editor is to love correcting other people’s writing. You trawl through a book and can see how you can improve it. Many editors (especially my wife Elaine) are much better at it (are much more meticulous) than I am, but I’ve kept on working over the years, sometimes successfully (as during the twelve years I received guaranteed freelance work from Macmillan in Melbourne) and sometimes disastrously (such as at the end of 1976, when I was actually forced to take a part-time office job for a year or so). Elaine and I have learned to skate along from cheque to cheque, and sometimes those cheques are very thin on the ground.

Bruce Gillespie and Elaine Cochrane on their Wedding Day (1979)

Q: In 1979 along with Carey Handfield and Rob Gerrand, you were one of the founding editors of Norstrilia Press, which published Greg Egan’s first novel, among others. Was there are particular philosophy that the three of you developed when you started Nostrilia Press?

Dick Jenssen and Rob Gerrand (2005)

Bruce Gillespie and Carey Handfield (1975)

A: Like the other small presses of the time, including Cory & Collins and Hyland House, our aim was to publish material that no major publisher would touch. You might remember that during 1973, for instance, there were 17 novels of any genre published by all Australian publishers. Even after the Australia Council began its publishing program under the Whitlam Labor Government, most of the spate of new titles sprang from the small press enterprises, such as Outback Press.

Carey said that the aim of Norstrilia Press (named in honour of American writer Cordwainer Smith, who had a great love of Australia, and whose only novel was Norstrilia) was to return enough money to SF Commentary, my magazine, to keep it going. This never happened, of course, but our first book (1975) was a set of essays called Philip K. Dick: Electric Shepherd. All the material, which included essays by Stanislaw Lem and George Turner, came from SF Commentary.

Carey devised a complicated system by which individual fans invested in particular books that we published. Since eventually we had to provide a return on investment, we diversified quickly. (Our only other critical book was The Stellar Gauge, essays by the finest critics in the field, edited by Michael Tolley and Kirpal Singh in 1981).

Our second book was The Altered I, with stories and essays based on the Ursula Le Guin Writers Workshop of 1975 (held in association with Australia’s first world convention, Aussiecon 1).

Our second book was The Altered I, with stories and essays based on the Ursula Le Guin Writers Workshop of 1975 (held in association with Australia’s first world convention, Aussiecon 1).

We tracked down a novel by Keith Antill called Moon in the Ground. It had won a prize several years before, but had never found a publisher.

Greg Egan sent us his An Unusual Angle, a brilliant novel he had written when he was seventeen.

I had met Gerald Murnane at Publications Branch, and had typed several of his novels before he learned to type. In 1977 I suggested that one section of a giant novel would make a great book on its own. That became The Plains in 1982, which was our greatest success (gaining a nomination for The Age Book of the Year Award), and still Gerald’s best regarded book. Text Publishing has just produced yet another edition, and it has had several overseas editions.

We were also very pleased to publish George Turner’s literary memoir In the Heart or in the Head, as well as The View from the Edge, his book about the 1977 Writers Workshop held at Monash University.

However, all of Carey’s and Rob’s labours were unpaid, and I was paid only for the typesetting work that I did for Norstrilia Press, Cory & Collins and Hyland House. At the end of ten years, we had made very little money, and Carey wanted to get married and establish his own career. So Norstrilia Press finished in 1985.

John Foyster, Carey Handfield, Damien Broderick and John Bangsund (1982)

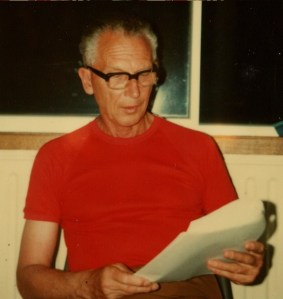

George Turner (1979)

Q: You are the executor for George Turner’s literary estate. What exactly does being a Literary Executor entail?

A: Not a lot, because George has not exactly been popular since his death in 1997. His main audience was overseas, and all those editions have gone out of print. Most of the work in keeping his name alive has been done by his agent, now my agent, Cherry Weiner, an Australian who has lived near New York for many years. At various times she has had great success with various Australian authors, such as Keith Taylor, Wynne Whiteford, David Lake, and now Paul Collins. She sold George’s posthumous novel Down There in Darkness, in 1998, but little since. I’ve signed contracts for Gollancz in Britain to republish The Sea and Summer (Drowning Towers in USA) as an SF Masterwork. I’m hoping that when it appears, it will re-establish George Turner as one of the major SF talents of the last fifty years.

I did publish 100,000 words of George Turner’s non-fiction as SF Commentary 76. Copies are still available, both as download and as a paper magazine.

Aussice Con 3 Timebinders Panel (1999)

Q: I was prompted to start this series of interviews because there seems to be a perception in the US and the UK that fantasy and particularly SF is a bit of a boy’s club. Do you think there’s a difference in the way males and females write?

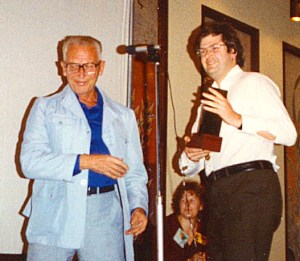

Bruce receives a Ditmar from George Turner (1980s)

A: Are we talking about science fiction or fantasy? To me they are quite different fields, with fantasy dealing with impossible events; and SF, at its best, being realistic novels that happen to be set in the future, rather than in the present or the past.

And are we talking about the writers or the readers? The balance in the composition of the readership changed very rapidly. When I became involved in SF fandom, the only women who turned up at conventions and club meetings were girlfriends or wives or members. That’s in 1968 and 1969. This began to change rapidly after 1971, mainly because of the influx of younger female media fans, but also a lot of women who were just beginning their careers as academics, teachers and librarians. By the 1973 Easter convention held in Melbourne, nearly half of the attendees were women, and that balance has remained even ever since.

But Australian writers, who were mainly male (Damien Broderick, Lee Harding, David Boutland, Jack Wodhams and Wynne Whiteford) tended to huddle in corners in the early 1970s because there were very few of them. There had been a very famous Australian female writer, Norma Hemming, but she had died in 1960 when she was very young. Cherry Wilder lived in Sydney for awhile, but she was a New Zealander with a German husband, so she went to live in Germany in the late 1970s.

The balance changed after fantasy became the dominant publishing genre in Australia in the 1990s. When HarperVoyager began consciously to recruit Australian writers, they found a treasure trove of young, enthusiastic women writers who have become very popular. Science fiction almost disappeared here, except from a few (male) writers such as Sean William, Sean McMullen and Terry Dowling. Marianne de Pierres and Lucy Sussex seem to be our only female writers who publish mainly science fiction.

All you have to do is look around at any fannish or professional gathering in Australia to see that 80 per cent or more of our writers are now female. They include many of my own favourite dark fantasy writers, such as Kaaron Warren, Cat Sparks and Deb Biancotti. I don’t read three-parter blockbuster medieval fantasy novels myself, but I acknowledge that Australia’s female writers (as well as a few males, such as Garth Nix) have conquered the field.

Q: Following on from that, does the gender of the writer change your expectations when you pick up their book?

Bruce receives the Chandler award from Paul Collins and Kirstyn McDermott (2011)

A: I’m only interested in finding good writing. I can’t help sympathising with Gerald Murnane’s rather provocative statement that no book should be published with the name of the author visible. In other words, the prose should speak for itself. Aesthetics über alles. However, like most readers I’m curious the find out about the authors whose works I enjoyed most, and I can’t help being flattered if my favourite writers remember something I might have written about their work. But I admit that most of my favourite SF writers have been male, for example, Philip Dick, Brian Aldiss, Thomas M. Disch, Cordwainer Smith, George Turner, Wilson Tucker, Stanislaw Lem and Christopher Priest. I always buy every new book by Ursula Le Guin. I love Joanna Russ’s work, but her novels were not as interesting as her short stories. I’ve enjoyed some of Gwyneth Jones’ books, but not all. In literary fantasy, nothing beats Le Guin’s Earthsea series and Diana Wynne Jones’s novels, but I also love fantasy by Peter Beagle, Italo Calvino, Steven Millhauser and a whole lot of others.

Q: And here’s the fun question. If you could book a trip on a time machine, where and when would you go, and why?

A: As the Strugatsky Brothers reminded us in their fun novel, Hard to Be a God, any of us would find any past era very smelly and very dangerous. Given the right inoculations (and nose filters), I would like to investigate the period that the Steampunkers have adopted as theirs, that very exciting era of huge change from 1880 to 1914. You would have to think that the First World War was staged to destroy that tremendous fizz of progressive thinking and scientific and artistic change that seemed likely to lead to a brave new world. How were they were to know in 1914 that millions would be killed, and that Stalin and Hitler would divide the world’s attention for the next thirty years?

For a list of Bruce’s publications and essays see here.

For Bruce’s listing on the e-fanzine site, with links to all his fanzines, see here.